21

It’s been a while since I blogged. The data entry job is long gone now, thankfully, and I’ve ‘left the office’. I don’t miss the constant sound of mouse clicking…clicking here, over there, a neverending cacophony of clicking. And the mindless, relentless boredom. But I miss the people I met. Originally I intended the diary to follow a typical day’s work, so this blog entry would have been about the final few hours in a day at the office, ending on that feeling of tired relief when you’ve done your time and can take off home, and leave the glare of the lights and strange sterility of the office behind. Instead, this post will be a few jumbled thoughts and recollections about working as a data entry temp worker, working in a low paid, near minimum wage, completely non-unionised white-collar workplace for a temp agency. This type of work and workplace is becoming more common, so it’s worth having a glimpse at everyday work and the potential for conflict in such places.

22

Management attempted its big speed up mentioned above in the last post, and bugger it, they mostly won. They got us to work faster through some pretty crude methods, although some work groups and individual workers held out. This was not unsurprising in today’s context of an incredibly low level of class struggle in NZ, but can some other more specific reasons be teased out?

23

For a start, the temp employment agency put us all on individual employment contracts which granted them all of the power. We had to sign the contracts or else we wouldn’t get the job. The contract outlined how we could get fired or disciplined for literally anything. At the end of long list of reasons why they could discipline us, including the normal insubordination and the like, there was a clause which said we could be fired or disciplined for anything not included in the list above!

24

If that was bad enough, there was also a specific clause which contained the ominous assertion we could be sacked or given a warning for not having a positive attitude!! In reality, ‘positivity’ could mean anything. Bosses could just bide their time, and pick on someone or some informal work group they disliked whenever they deemed they were not being ‘positive’. And when you are working a mundane, repetitive data entry job – a ‘bullshit job’ if there ever was one – you don’t exactly feel positive most of the time. The work by its very nature was not fun and positive, it is mundane, zombiefying and absurd. It is as if management think if just we just become happy shiny positive little automations this data entry work will somehow become fun. If you think this clause is absurd, and would have never be used by management, think again. At least one worker was fired for having a poor attitude as far as I am aware.

25

Management believes that the ‘positive atmosphere we [i.e. the team leaders] created at the start’ meant that there was not a high turnover of workers (this was an actual quote from a team leader during my ‘assessment’, which involved being taking aside and told to work faster). Yet I got the impression that most workers saw through their simplistic, crude propaganda and feel good manipulative ‘energising’ techniques were seen through right from the start. Maybe some bought into the crude ‘pumping up’ and bullshit talk about how wonderful it was to be here, how great it is to be part of a team, what an important job you are doing, and all the collective exercises complete with upbeat music and stupid motivational talk. But most didn’t. We were there for one thing: money. And as my co-worker pointed out ‘that’s bullshit [that a positive atmosphere stopped people from leaving]. We didn’t leave because there are no other jobs.’ Unemployment is high, and jobs are scarce. So most put up with all the ‘smile or die’ positivity bollocks, the quizzes and exercise breaks, because at least we are getting paid for it. Anyway, as the job went on after a few months, a few left after they got new jobs, and during the breaks and sometimes during work time people openly talked about how they were looking for other jobs, occasionally even to team leaders.

scary positivity in the office

26

Perhaps the most surreal part of the day was the exercise breaks, which formed a core part of the positivity bollocks they tried to enmesh us in. We had two such ‘breaks’ a shift, at about 2 hours in, and 2 hours before the end of a shift. The exercises took place in the ‘break out’ area (namely an area where we had our lunches and cuppa tea during our real breaks). We would line up and face a hyped-up team leader together with a couple of willing cronies who would stand up the front, like at a gym. Then they would go through the weird routine of the gym: pep talk, playing loud, upbeat music (which was given some sort of democracy because workers could choose what to play themselves) and then into the exercises. A few gym junkies liked it, and most of us put up with it, maybe a bit embarrassed at first at just how silly it was (particularly the more weird exercises, like pretending to swim, and twirling your arms around in circles). But as the job went on an increasing minority grew to loathe the exercises. A few of us went to the back where they couldn’t be seen very well, or took long toilet breaks, or faked injuries. Some people occasionally stood behind poles where they couldn’t be seen at all, and just read magazines. But the most common form of resistance was when a group of work friends did the exercises with little enthusiasm, or barely did them at all, while all the time chatting to each other and ignoring all the histrionics emanating from the front. A lot of us made fun of the instructor barking out the enthusiastic orders, and many refused to do certain exercises which seemed humiliating or silly. This lack of enthusiasm did lead to conflict, with the team leader calling out individuals for harassment during the exercises if they were not doing them well enough. People did fight back a bit, and still continued to do the exercises poorly even in the face of warnings from team leaders, but overall it was not a major site of conflict, unlike the speed up.

27

A major reason why people disliked the exercises was that they were absurd: they were not really designed to help us, but more designed to stop any legal action against the temp agency for things like repetitive strain injury, namely injuries to our wrists and fingers through repetitive clicking (which did happen to a few people just after a few months at the job), and sitting in our seats for too long, straining our eyesight and backs. The absurdity of the exercises here was that they were not designed to help our wrists, fingers and hands, or our backs, but instead were something out of a football exercise manual! The whole thing reminded me of being at school again in phys ed class, rather than specific ones for office work. They didn’t take actual health and safety seriously, and just reduced it to advice about not tripping over power cords and the like. Office work, while nowhere as dangerous as manual work, is a pain if you do it for years on end, and often leads to bad backs, RSI, poor eyesight, and the like. These injuries tend to be hidden but I reckon you ask most people who have worked in an office for 15 or 20 years they would have suffered from one of them.

28

Onto the big speed up. At first, we are ahead of schedule. The work is easy. So most agree on the need to slow down, including some team leaders. Team leaders even devise ‘team games’ and give us half an hour off early in order to slow us down. But one young nerdy guy wants to push himself, and aims to do 3 times the set work rate. This leads to open arguments. ‘You’ll put us all out of work’ ‘if you work harder you will reduce our pay’ by getting the overall job done before time (if the job was completed a few weeks early, we will lose a couple of weeks pay). He ignores the arguments and says he wants a reference, it is only the second job he has had, and it is a step up from his previous job in the Warehouse – and he explicitly says he only cares about himself, and not others. These sort of internal conflicts will come more to a head when the pressure is put on.

29

A new manager is appointed, promoted from being a team leader. She claims that we are now actually behind on schedule. So she enforces a new mean regime based on a big speed up. Oh the irony, because when she was a team leader she was encouraging people to slow down. We are sternly told we are slacking off, talking too much, our ‘numbers are down’, and we come late back from breaks. Perhaps the real reasons behind the speed up are probably to get the work completed a few weeks before the temp agencies contract with the firm that wants the statistics is over, so the agency can save all that money and our pay; and also her head is now on the line. So new targets are enforced: 2500 forms to process per work group in an 8 hour shift, 250 per head. Targets are written up on a board, but thankfully only work team numbers are put up there, not our individual ‘outputs’ like in some call centres. People are pulled up for arriving to work or back from lunch just a minute or two minutes too late, and a crude regime of rewards for ‘person of the month’ in each ‘team’ is introduced. Yet when we begun the job, we were indoctrinated into the need for ‘quality statistics’ and making sure we got things right. But now, as one workmate says to me, ‘it’s all about the numbers.’ So quality begins to drop off. It’s all about getting the work done fast; management doesn’t care about quality any more.

30

Some speed up – they tend to be the young and inexperienced individualistic types who are concerned about themselves (and their job reference), and not anyone else. Maybe they also want ‘to prove themselves’. A few are out to impress as they want to get promoted and become a team leader if a position becomes available. As well, many young people treat the data entry work like a video game, as if they have to dismiss problems as fast as possible, as if they as going for a high score, just like that nerdy guy. They looked wired and intense at work, like when they are playing. This is encouraged by team leaders, who constantly up their individual targets. (This is not to write off young people, who are often the most rebellious in the history of class struggle – in NZ the young workers who don’t have kids and mortgages and the like are often the ones with least to lose, and probably more likely to struggle – and I found quite a few young workers to be subversive, and willing to fight but just had little experience of how to do it in a very difficult climate, how to bring others on board and get people working together. For example, one young guy said to me ‘temp agencies are like cancer, they drive down wages and conditions’ but he did seem to know how to fight them.)

31

But others do not speed up – especially the older workers, who have a bit of work experience and know that if you increase your work speed, they will just keep increasing your targets, until you are worn out. Which is exactly what management did, of course. Many of the older workers say you can’t keep working fast all the time, as you will get burnt out. So they say ‘I will just do the same numbers I have always done’, reasoning you don’t get more pay for it. They find a comfortable level that they are happy with, and stick to it. But generally they just keep to themselves, and do not encourage the younger ones to slow down, maybe hoping they will learn through experience.

32

One older worker did attempt to get the fast, individualistic ones to go slower, and did get a few people in their particular work group on board, but the plan was upset by a fast young worker out to prove herself by going as fast as possible. So it is very difficult to get some collective action going. Obviously, some sort of informal collective go-slow, or at least limiting of the speed up, was needed. The new manager is unpopular, and speed up puts much pressure on some people. We talk, on our way home, or on breaks, about how to reduce work intensity, how awful management is, how absurd the work is. The talk is refreshingly open and critical, compared to working in some jobs where you have to be very careful what you say and when you say it, because it could be reported to management. But does still lead to open resistance? A sort of everyday war over work intensity does occur. Yet, again, individual coping strategies were mainly used, and only a few collective slow downs occurred between some small circles of work friends. A big problem is that because the work is so boring, some work fast just as a means of coping with it: they need a fast numbing rhythm to get thru it, if they stop and think it makes things worse, so it seems to me a few welcomed the speed up. Myself, I have to admit I initially got swept along with the speed up like almost everybody, even though I didn’t want to speed up at all. You know it is wrong to speed up for all the reasons above, but somehow you think jeepers most people are speeding up here, and I don’t want to get in more trouble, so I will have to go quicker so my ‘output’ is not so low. But after a while, I realise this is silly, I can just set an easy pace and encourage others to do so now and then.

33

When the pressure was put on everyone to increase their targets, people find ways to increase our outputs without doing much work. Some ‘up their stats’ simply by short cutting their work, by not filing certain forms correctly, but it looks like on the system they have completed the problem. Also, people can send through many of our problems that take a long time to do on to a specialist work group that deals with problems that are ambiguous and hard to answer. While team leaders can monitor your individual output, they can’t tell exactly what you are doing with the individual problems, so this is possible. However, some (especially the more ‘nerdy’ ones who want to ‘up their stats’) do this to such an extent that they don’t do anything but the easiest of the problems, ones that take only 10 seconds or less to solve, and this creates resentment that they are not pulling their weight.

34

Part of the speed up is to pick on workers who are working too slow, but again, this is applied unevenly as some team leaders just recognise that is the speed people are capable of. Some workers deemed too slow are dragged into meetings, and offered ‘training’ to work faster, with the threat if they don’t work faster warnings and the sack is around the corner). Yet still some slowbies resist. However, some workers again see the ‘slow’ workers as problems, bringing the team statistics down. There is a general lack of goodwill to everyone. That workplace reminded me of school in more ways than one.

35

Part of their divide and rule tactics that make resistance difficult is how they move people around from seat to seat in their work groups. They move people around every 3 weeks or so, so you have to sit at a different desk and get to know new people. This is particularly the case when they notice strong friendships develop between workers, and you talk too much to certain people. This is incredibly frustrating as it feels like you’ve just got to know the people sitting beside you. You can get around it a bit, by talking to your mates during the breaks and lunchtime, but still you need somewhere to natter away with on the job. Yet a good side of being moved around is that you are forced into nattering to the new people you sit beside after a while, I found, or else the boredom would set in. A few people remain quiet and I wonder how they do it.

36

The speed up does lead to morale starting to crack though, and many start to grumble. You get the feeling if we were pushed further, or another absurd twist to this job (being told it was all about quality but then told it’s all about working fast) a collective fight back would have occurred, and management would have had to pull back in some ways. If the job had maybe lasted for 6 months I think such a fight back would have occurred. It would have been messy and uneven, but many would have taken part.

37

Although we wield more power than we thought on the office floor, most workers didn’t realise it. The majority of the workers were very young (under 25) and inexperienced. For some, it is their first job. Probably a majority have university degrees, so have high expectations that they are going to get well-paid and somewhat stimulating jobs, so this is what is called ‘not a real job’ for them, just an ‘in between’ job before they supposedly get those well-paid and somewhat stimulating jobs (that mostly doesn’t happen, of course). Overall, my impression was that few had experienced open workplace conflict, or collective struggle, or even unions for that matter. A lot are just shuffling around from temporary contract to temporary contract, so think that they will just put up with things if they get bad, because in a few months they will be working somewhere else (or on the dole queue). The workforce was multicultural – a majority were white, yet a substantial minority were Maori, Samoan, Cook Island, Tongan, Indian, and Japanese. A few are migrants from Britain, Zimbabwe and Eastern Europe. The workforce was also evenly divided between female and male workers. Peoples political views are diverse, ranging from right wing to far left. Most of the young workers don’t have firm politics, with some coming across as a bit nihilist. Yet this diversity did not create problems between workers, as most people got on pretty well. But in the short time we were there (the job lasted 4 or 5 months) it was difficult to build lasting communal bonds between all the workers (while of course a few solid cliques formed). This was especially difficult on the job with the management technique of moving people around all the time.

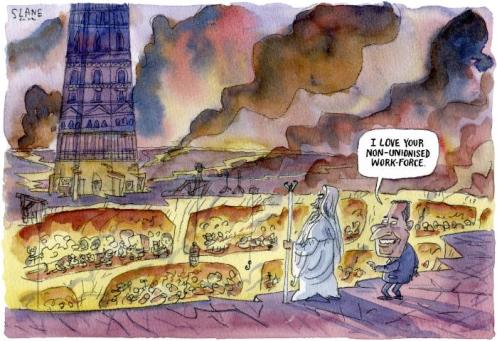

Management view of an office

38

Yet, at the same time, there were plenty of reasons for collective struggle. The work was intensely boring. Management were pretty shambolic and ad-hoc, we had no say in what was going on, but had the pretence of ‘consultation’ now and then. Overall management treated us like school kids: they thought we were dumb and thick, in constant need of being monitored, and constantly making mistakes. Just like school, the team leaders had a few ‘naughty girls and boys’ who they picked on, and used as examples to keep others in line. One technique was to put the ‘naughty ones’ in ‘hot seats’ right next to the team leader who could directly look at their screens. Their work gets closely monitored and commented on. This is a familiar technique – it is common in many offices I’ve found, to put the worker deemed too rebellious in the most exposed place in the whole open office, so they can be seen and monitored (one guy who I met in another job said he was put right in the middle of an open office where his work behaviour was in the line of sight of 3 managers). As well, team leaders take on board ‘teacher’s pets’ who have buttered up to the team leader and thus were considered angels no matter what they did. Thus they could get away with more. And the super fast workers who treated their jobs as a computer game were never disciplined for being inaccurate. Of course, this crude favouritism suits management perfectly, as it is a classic and tried and tested form of divide and rule (and I’ve found it in all the offices I’ve worked in, including ones where the workers have permanent jobs in the ‘public service’).

39

Overall, it was the messy, contradictory tension between inexperience and a crude disciplinarian management (and behind it the dictates of capitalist exploitation, as management has to follow the dictates of capital) that created a messy, contradictory workplace, one in which there was lots of subversion, but little of it was collectively organised. I have written this to perhaps try to understand a wee bit why there are virtually no strikes in New Zealand today – despite there being falling real wages, widening inequality, restructuring due to the global recession, strange human resources management techniques being thrown on workers, and productivity speed ups. The answer is complex – a combination of capital having enormous power over workers (eg. through individual contracts and a constantly recycled precarious, temporary workforce), high unemployment, little job security, low expectations, widespread inexperience in successful class struggle for young workers and so on (as outlined above) all make it very, very difficult to struggle. Yet we shouldn’t write off all workers as compliant, individualistic and obsessed with gaming, facebook and the like, and then rabbit on about how the working class has disappeared/been restructured/decomposed, and how workers’ identity, culture and class consciousness has been lost, and then launch into some form of nostalgia about how great class conflicts were in the past, or mythologise some group like the NZ IWW, or argue what is really needed is ‘a fighting union’. A lot of these critiques, while they contain many grains of truth, are based on critiques from afar, on abstract theories like for example the communisation current. I get the impression these theories are the product of a few intellectuals who look from the outside on workers, and often down on workers (although I agree there is a real need to re-assess working class politics today in the light of the ongoing and quite successful assault by capital since the 1970s). It is not like I am an expert in all this, I am continually learning from my experiences (and those of others too) and making mistakes; I don’t claim to really know, or have greater insight or experiences, than the vast majority of other working class people. Or that I think, in a moralistic way, that people must take jobs in offices or factories or whatever. But I do think there is a need for politics to be based on the actual everyday conditions we experience, and the messy contradictions of them – ie. for politics not be based on gazing or condemning from afar, but on the actual, real conditions people face today. And part of that dealing with current conditions is to find out how modern office work actual works, and how working with temp agencies in temp jobs works, and how these modern forms of capital are actually an area where the contradictions of capital still exist, rather than assuming capital has completely won, dismissing all office or temp agency workers as having no potential for class struggle, and lamenting the decline of the traditional blue collar work and identity and so on. I once wrote: ‘Strategy is more effective in the long term if it is the product of workers’ direct experience and struggles. That is, a well-thought out strategy just builds upon the actual strategies used by workers on the shop floor, except in a more clear, systematic and coherent way. If strategies are not a product of workers’ direct experience or actual struggles, then they are likely to become either artificial and lacking any support (eg. setting up “pure” anarcho-syndicalist unions) or lead to a top-down approach where workers are manipulated by a few bureaucrats, organisers, delegates or politicos.’ To that we can add abstract theory which claims to have a grip on the actual conditions we face under capital today.

Posted in Bluddy orrible office work, Class, Class recomposition, Precarious labour

Tags: office boredom, panopticon office, positivity, smile or die, team leaders, work faster and shut up